This article is part of our According to the Data series.

Predicting Breakouts from Young Running Backs

"Running backs need to be quick, not necessarily fast. Quickness matters more than straight speed."

- Every NFL television analyst ever

In theory, it seems to make sense that running backs would benefit more from quickness than straight-line speed. They frequently work in traffic and certainly need the ability to make defenders miss in tight areas.

But I've shown in the past that straight-line speed, measured by the 40-yard dash, is highly predictive of NFL success for running backs. The running backs who post the best numbers continually run better than 4.50 in the 40-yard dash.

Yes, there are outliers. But for every Alfred Morris you can name, I can name five Ray Rice's (4.42, believe it or not).

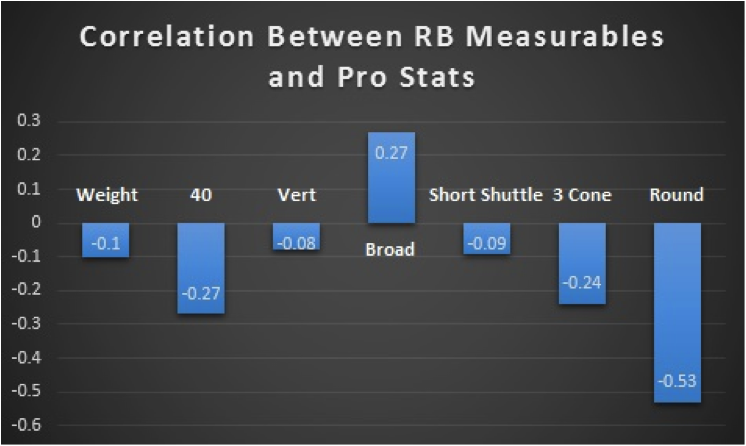

In addition to speed, I want to see which other measurables might be predictive of NFL success for backs. So I charted some NFL Combine numbers for every running back drafted between 2008 and 2012. Then, I compared those numbers to each back's approximate value per year - an awesome judge of production on a per-season basis (so younger running backs aren't penalized for playing only a couple seasons).

The Correlations

Check out the strength of those relationships. Note that there's a negative correlation for every measurable except for the broad jump. That just means the longer a running back's broad jump, the greater his NFL production. Meanwhile, the lower the back's weight, 40 time, vertical, short shuttle, three-come, and draft round, the better

Predicting Breakouts from Young Running Backs

"Running backs need to be quick, not necessarily fast. Quickness matters more than straight speed."

- Every NFL television analyst ever

In theory, it seems to make sense that running backs would benefit more from quickness than straight-line speed. They frequently work in traffic and certainly need the ability to make defenders miss in tight areas.

But I've shown in the past that straight-line speed, measured by the 40-yard dash, is highly predictive of NFL success for running backs. The running backs who post the best numbers continually run better than 4.50 in the 40-yard dash.

Yes, there are outliers. But for every Alfred Morris you can name, I can name five Ray Rice's (4.42, believe it or not).

In addition to speed, I want to see which other measurables might be predictive of NFL success for backs. So I charted some NFL Combine numbers for every running back drafted between 2008 and 2012. Then, I compared those numbers to each back's approximate value per year - an awesome judge of production on a per-season basis (so younger running backs aren't penalized for playing only a couple seasons).

The Correlations

Check out the strength of those relationships. Note that there's a negative correlation for every measurable except for the broad jump. That just means the longer a running back's broad jump, the greater his NFL production. Meanwhile, the lower the back's weight, 40 time, vertical, short shuttle, three-come, and draft round, the better his production.

Let's take these one at a time.

Weight: There's a very weak relationship between weight and pro stats, likely because lighter running backs can run faster. Weight itself isn't inherently disadvantageous, it seems, but it becomes a problem when it slows a running back down. More to come on this.

40-Yard Dash: Not really a surprise here. The 40-yard dash is the second-most predictive trait for running backs, behind the round in which they were drafted.

Vertical: The negative correlation is surprising and obviously just noise. If a lower vertical jump actually helped players perform better, I'd be in the NFL. However, I think the data definitely suggests something I've had a hunch is true; the vertical jump doesn't matter. It doesn't capture true explosiveness, which is what's important for running backs.

Broad Jump: The broad jump is the most underrated physical test out there. Most NFL teams seem to care more about a player's vertical than his broad jump, but I've found that there's an extremely strong correlation between broad jump and 40-yard dash time. Both measure explosiveness in a way that the other tests can't.

Short Shuttle: There's no significant correlation between short shuttle time and running back success.

3 Cone: Surprisingly, the three-cone drill is much more strongly correlated with running back production than the short shuttle. I'm not sure I have an answer for this outside of the three-cone just being a better judge of explosiveness and change-of-direction.

Round: The strongest correlation of the bunch, by far, is between production and the round in which a back was drafted. This is all about highly drafted backs seeing the field more than mid and late-round picks (and it has almost nothing to do with actual talent).

Either way, a first-round running back selection will typically produce quality fantasy numbers just because he's going to see a heavy workload. The fact that he's not an outstanding player might not matter all that much in the short-term.

Weight and Speed

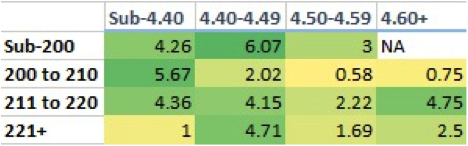

The moderate negative correlation between weight and NFL production for running backs was surprising, but I figured it's due to lighter running backs being faster and skewing the results.

So I charted every running back into one of 16 groups based on his speed and weight. Here's a heat map of the results, with darker being better:

You can see an obvious relationship between speed and running back success; almost all of the dark green boxes are near the left side, i.e. the speedsters.

However, there's not really too much of a relationship between weight and production, even after accounting for different subcategories of speed. That doesn't mean that extra weight is a bad thing (assuming the speed remains the same), but just that it appears to be less of a factor than what you might think.

If given the choice between a 220-pound back who runs a 4.45 and a 200-pound back who runs the same, I'm obviously taking the heavier player. But if we're talking about a 220-pound back in the 4.55 range, I'll take the lighter back all day long. Weight is great, but I have a need for speed.

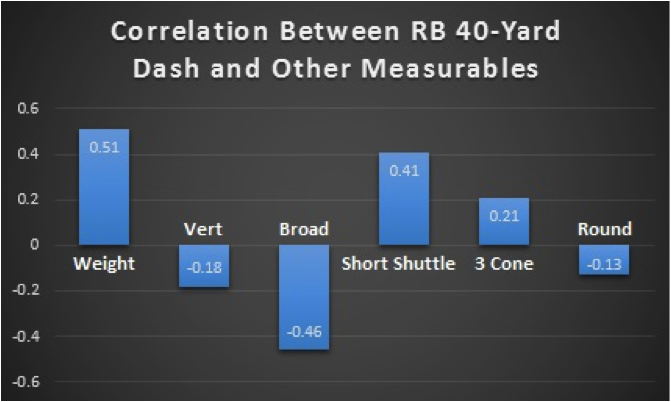

Relationship Between 40-Yard Dash and Other Metrics

To better show why the numbers are the way they are, I want to take a quick look at the correlations between each measurable and the 40-yard dash. Remember, a player's numbers aren't independent of one another; weight affects speed, explosive players will test well in a number of areas, and so on.

The strongest relationship here is unsurprisingly weight and speed; the heavier a running back, the slower he'll run. There's a mild correlation between the vertical jump and 40-yard dash, and the same goes for the three-cone drill.

Meanwhile, check out the strong relationship between the 40-yard dash and broad jump. Those backs who typically run really fast can also jump very far. The broad jump is more strongly correlated with the 40-yard dash than the short shuttle, which many might not initially assume to be true since the latter two are both tests of speed.

This is all pretty good evidence that we should be using the broad jump more in our assessment of running backs. It's perhaps just as good of an indicator of explosiveness as the 40-yard dash.

When a running back runs really fast but has a poor broad jump (Johnathan Franklin, for example), it might be a sign that he isn't quite as explosive as we think. If a back has only a decent 40-yard dash time but an outstanding broad jump (Michael Ford, for example), we might want to reconsider him as a potentially explosive running back.

Last, take a look at the relationship between the 40-yard dash and the round in which a running back is drafted; there's actually a negative correlation, meaning NFL teams have drafted slower running backs first!

You might take the strong correlation between draft round and production as evidence that teams are "getting it right" on running backs, but don't forget that the production is dependent on a heavy workload, which early-round backs obviously get.

In reality, running backs drafted in the late rounds have actually been more efficient than first and second-round backs on a per-carry basis! NFL teams are so bad at drafting running backs that you could completely randomize the order in which the backs get drafted and it wouldn't change much.

With the manner in which the 40 predicts running back success, it's absolutely shocking NFL teams aren't valuing speed more in their assessment of running backs, and it stands as clear evidence that most NFL organizations still just don't get it.

Jonathan Bales is the author of the Fantasy Football for Smart People book series. He also runs the "Running the Numbers" blog at DallasCowboys.com and writes for the New York Times.