As a writer, one of my favorite things to do is dispel "truisms" that exist within the sport of football. "Never take points off of the board" and "you run to set up the pass" are two long-held beliefs that simply have no basis in reality. There are lots of times you should take points off of the board, and in today's NFL, teams really don't need an effective running game to win. Yeah, I said it.

In fantasy football, there are a plethora of "truisms" that many owners use as a basis for creating their rankings. "Wide receivers tend to break out in their third season" and "you can always wait on a quarterback" are two of the most popular.

Today, I'm going to take a look at the merits of avoiding running backs coming off of seasons with huge workloads. Many fantasy owners believe that, following seasons in which running backs touched the ball often, they tend to break down, often getting injured or seeing a decrease in effectiveness.

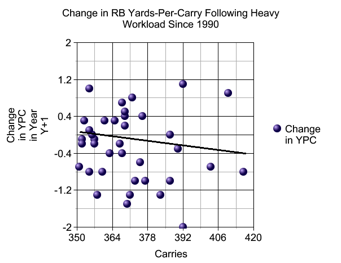

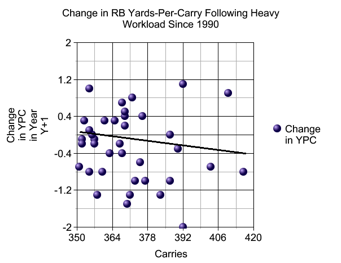

I researched the production of all running backs with 350 or more carries in a season, and the results are below.

You can see that when running backs record 350-plus carries in Year Y, they generally see a decline in yards-per-carry in Year Y+1. Of the 37 running backs to generate 350 carries since 1990, 24 (64.9 percent) produced a lower YPC number in the following season. The average decline in YPC was 0.26 for all backs, 0.38 for

As a writer, one of my favorite things to do is dispel "truisms" that exist within the sport of football. "Never take points off of the board" and "you run to set up the pass" are two long-held beliefs that simply have no basis in reality. There are lots of times you should take points off of the board, and in today's NFL, teams really don't need an effective running game to win. Yeah, I said it.

In fantasy football, there are a plethora of "truisms" that many owners use as a basis for creating their rankings. "Wide receivers tend to break out in their third season" and "you can always wait on a quarterback" are two of the most popular.

Today, I'm going to take a look at the merits of avoiding running backs coming off of seasons with huge workloads. Many fantasy owners believe that, following seasons in which running backs touched the ball often, they tend to break down, often getting injured or seeing a decrease in effectiveness.

I researched the production of all running backs with 350 or more carries in a season, and the results are below.

You can see that when running backs record 350-plus carries in Year Y, they generally see a decline in yards-per-carry in Year Y+1. Of the 37 running backs to generate 350 carries since 1990, 24 (64.9 percent) produced a lower YPC number in the following season. The average decline in YPC was 0.26 for all backs, 0.38 for the top 20 backs (in terms of workload), and an incredible 0.51 for the top 10 backs.

A decrease of 0.51 YPC from one season to the next is a pretty hefty number. At first glance, it really appears as though a high volume of carries can have adverse effects on a running back's subsequent season.

As with many things in fantasy football and life in general, looks can be deceiving. Whenever collecting stats, it is important to determine how representative the group is of the whole. If you poll 1,000 people regarding this year's presidential election, you'll get vastly different results if you perform one poll in the heart of Alabama (no offense, fellas) and the other poll in Vermont.

When a group of stats isn't representative of the whole, it is known as a selection bias. A selection bias is at work when we analyze running backs coming off of seasons with heavy workloads, and it can lead us astray when making conclusions about those backs' future effectiveness.

For a running back to acquire 350 or more carries in a season, a lot of things need to go right. He needs to be healthy; it's simply a prerequisite for receiving so many touches. Of the 37 running backs who have gotten 350 carries in a season, the total number of games missed was five combined. Only five missed games out of a possible 592 played!

Secondly, the running back necessarily must maintain a certain level of efficiency. Without it, he won't keep acquiring so many touches. If Chris Johnson is averaging 3.0 YPC after eight games this year, for example, you can bet he won't be getting the ball nearly as much in the second half of the season. Of the top 15 running backs in single-season carries since 1990, only two have averaged less than 4.3 YPC. Nine of those 15 were above 4.5 YPC.

Knowing that the selection of backs with 350-plus carries in a season is naturally skewed toward those that were healthy and effective has profound implications on our conclusions. Naturally the outliers from the previous year, these backs are likely to regress toward the mean, independent of their workload. That is, running backs who have a high YPC are likely to regress in the following season whether they got 350 carries or 100.

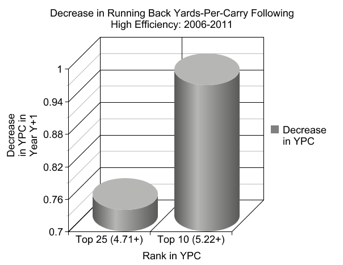

That idea is supported by the stats. When examining the relationship between YPC in Year Y and Year Y+1 among all backs, we see a trend similar to that of the high-workload rushers alone.

Above, you can see the dramatic decline in efficiency among the NFL's most effective runners over the past five years. Heavy workload or not, running backs coming off of seasons in which they recorded a high YPC almost always saw that number drop in the following year. Of the 25 backs to average 4.71 YPC (on at least 180 carries) from 2006 to 2010, only three (12.0 percent) increased their YPC in the next season. The average decline was an astounding 0.74 YPC. Of the 10 backs to average 5.22 YPC, the average decline was almost a full yard on each carry.

Ultimately, running backs coming off of seasons with lots of touches are likely to regress in terms of both efficiency and health, but that information is both insignificant and irrelevant to fantasy owners. Since high-carry running backs are outliers from the previous year, all you're really saying when claiming that "running backs with X carries in Year Y see a decrease in health and YPC in the following season" is that running backs with unusually good health and an abnormally high YPC are likely to have worse health and a lower YPC the next season. Yeah, duh.

Thus, while the production of a running back coming off a season with a heavy workload is likely to decrease, it is not a legitimate reason to avoid that player in fantasy drafts. The (probable) decrease in production is due to the previous season being a statistical outlier (a result that is unusually far from the mean).

The best way to look at the situation is this: what is the running back's chance of generating production that is comparable to the previous year's? It is actually the same as it was prior to the start of the previous season, i.e. the workload has no noticeable effect on his ability to produce.

For example, if a running back has a 20 percent chance of garnering 2,000 total yards in a season, that percentage remains stable (assuming his skill level does the same) from year to year. Thus, the chance of this player following a 2,000 yard season with another is unlikely, but not due to a heavy workload (a necessity for such productive output), but rather the fact that he only had a 20 percent chance to do so from the start. We wrongly (and ironically) attribute the decrease in production to the player's prior success when, in reality, no such causal relationship exists.

So when deciding whether to draft Ryan Mathews or Ray Rice this year, there's no reason to choose Mathews simply because he had 69 fewer carries in 2011. In reality, the odds that Rice stays healthy and puts up big fantasy numbers are around the same as they were last season.

Jonathan Bales is the author of Fantasy Football for Smart People: How to Dominate Your Draft. He also runs the "Running the Numbers" blog at DallasCowboys.com and writes for the New York Times.

You can follow him on Twitter @TheCowboysTimes.